The CURATION Of: Musée d'Orsay

Visited 10/11/2022

The Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Across the Seine from the Louvre lies a building that was once a palace (Palais d’Orsay), railway station (Gare d’Orsay), hotel (Hôtel d’Orsay), and since 1986, a museum - Musée d’Orsay. Its transformation into the art museum it is today was a solution necessary for opening a space which bridged the gap between artworks in the Louvre and the Centre Pompidou. Musée d’Orsay became the location which housed paintings and sculptures created between 1848 and 1914 of mainly French origin. Its beautiful, curved, glass roof and platform length architecture fashions a surprisingly suitable, grand display of art.

Due to the long, open structure of the museum, walking around the ground floor requires a lot of back and forth to see everything. While Impressionist works were all grouped together in a massive collection on the fifth floor, the ground floor and the second floor involved much smaller rooms of various styles and specific periods/artists. On the ground floor then, these small yet incredibly lively paintings stood out to me. Their academic and classical styles exude high French society in a theatrical, exclusive, and alluring manner. Prince Napoléon’s Pompeii-inspired palace, now destroyed, is immortalised by Boulanger. Jean Béraud grew popular amongst the French public for his depictions of Parisian city and night life. His painting of the French upper class in A Ball isolates the viewer, where the central figures have their backs turned to us. Extraordinary detail in Gérôme’s painting captures the exceptional military prowess of 17th century France.

Gustave Courbet’s painting with the full name The Painter's Studio: A real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life adorns an entire wall of the Musée d’Orsay. This large-scale painting with a fascinating title tells a story of many parts about Courbet. He sits, at the centre, painting a landscape in the style of Realism, with his back turned away from a nude model behind him, who represents Academic art. On the floor to his left are a cluster of items: a dagger, a guitar and a plumed hat. These represent Romantic art. Academicism and Romanticism were two prominent movements in 19th century French painting which Courbet rejected, in favour of Realism. Further details include people on the left depicting figures from all levels of society, while those on his right were his friends, associates, and most importantly, his patron Alfred Bruyas. Then, your eyes probably turn to the ambiguous background which looks rushed and unfinished. Courbet had a deadline to complete this painting in time for the 1855 Paris World Fair, originally planning to paint small replicas of other works of his to fill up the wall. In the end, he had run out of time to finish the idea and so covered them up, though some of the paintings are still fairly visible.

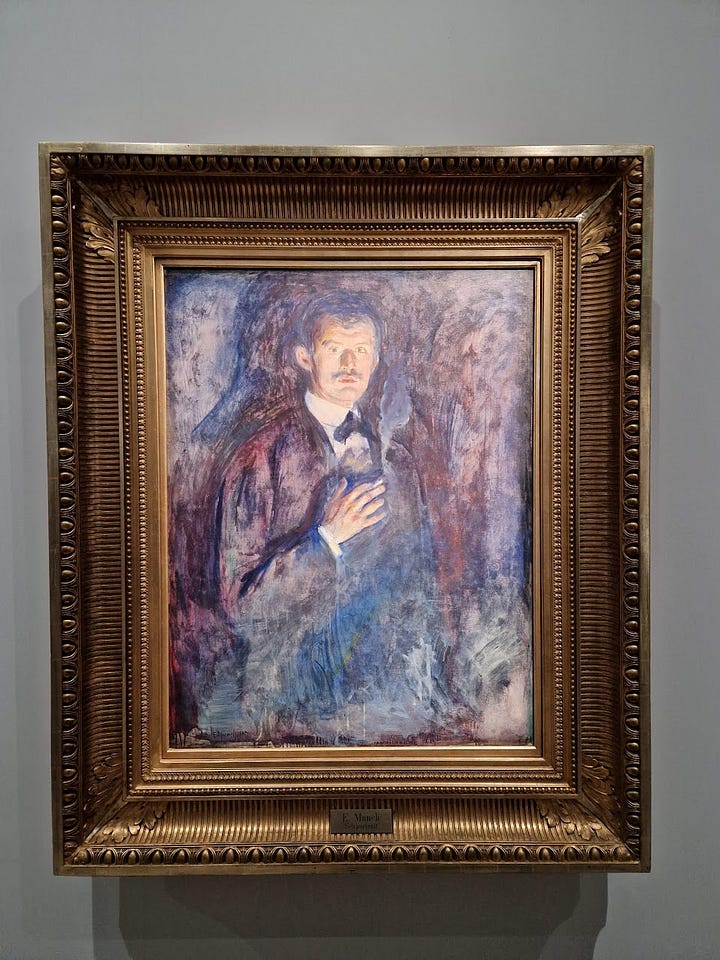

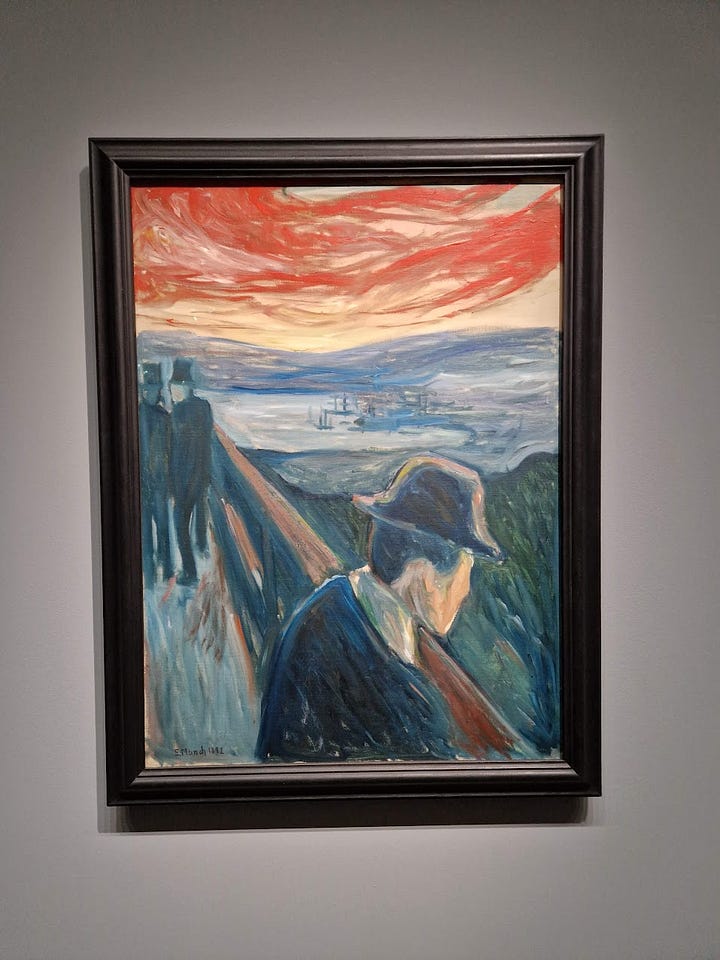

To the left of Courbet’s The Painter’s Studio is one of Musée d’Orsay’s exhibition spaces. Coinciding with the time of my visit, on show was ‘Edvard Munch: A Poem of Life, Love and Death’. Munch’s artworks are organised into a project he called The Frieze of Life. The artist explored and expressed emotions in a raw and repeated form. His paintings on disease and death are marked by his personal struggles in facing them, for members of his family succumbed to the latter or at least the former, from as early as when Munch was five years old. Munch himself was ill throughout his childhood. His works, described by the artist as a series and a continuation, can be observed autobiographically and are all in dialogue with each other.

Up onto the second floor and the first room you walk into is a preserved ballroom from when the building used to be a hotel. In this emptied out sneak peek of Beaux-Arts extravagance, you can imagine yourself stepping into a Parisian ball, like the earlier painting by Jean Béraud. Though indeed, this spectacular hall is open for hire… The olive branch chandeliers are a uniquely mesmerising highlight.

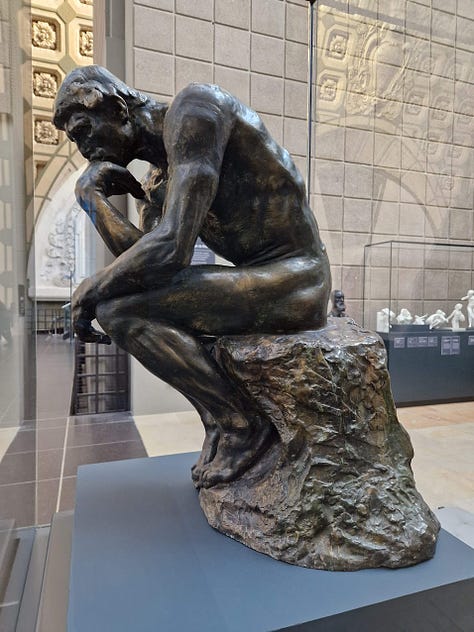

One of the most recognisable works of art, let alone in sculpture, let alone in French sculpture, Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker is humorously and aptly placed, overlooking the stretch of the museum. Directly behind, and thus also towering Musée d’Orsay’s interior, is Rodin’s The Gates of Hell of monumental size and feat. The Gates of Hell is Rodin’s depiction of a scene in Dante’s poem Divine Comedy, commissioned by the Directorate of Fine Arts in 1880, though Rodin worked on this project for 37 years, up until his death in 1917. It is from this large-scale sculpture which The Thinker as a standalone subject originated. He is visible, sticking out the top centre in The Gates of Hell, just like how the sculptures have a commanding sight over the museum. As such, it is still in contention whether The Thinker represents Dante or Rodin himself. Less in contention, however, is the French sculptor’s celebrated status as founder of modern sculpture.

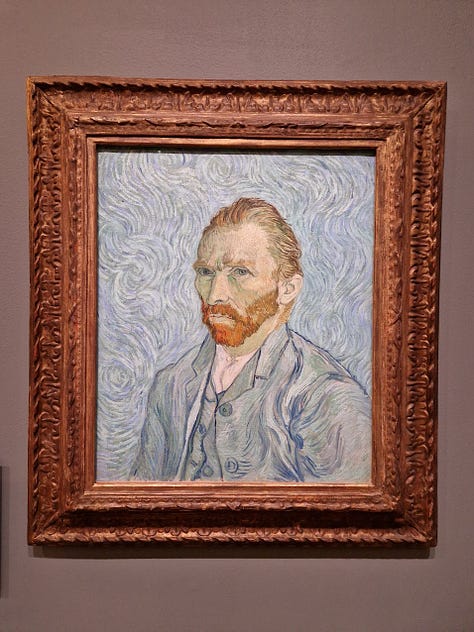

Musée d’Orsay boasts having the largest Impressionist collection in the world and rightfully so. Residing in the birthplace of the art movement, this museum was built specifically to give a home to artworks of this period. Almost the entire fifth floor is dedicated to Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

The first major artwork is Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass. While this painting is not distinctly Impressionist, it reflects the transition of stylistic favour from Realism to Impressionism. The main divisive quality is in the clearly visible brushstrokes. Manet’s works, starting with this one, became a prime influence for many Impressionist/modern painters. On the directly opposite wall, contrarily displayed by Musée d’Orsay, is Monet’s interpretation of the same title.

Another highlight masterpiece of the collection is Renoir’s Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette. The scene depicts working class Parisians dressed up to dance, drink and eat in the sunny outside. Renoir’s artistry is characterised by a vibrant portrayal of natural light, saturated colours, and candid figures who blend with their surroundings. Patches of sunlight bleed through the trees and generously lightens the mood of the scene. The painter’s technical expertise shines in this Impressionist sensation.

Above are more captivating paintings which I picked out from the Impressionist floor. As always, with these massive collections, there is only so much I can divulge when writing my reviews. But truly, it is difficult to find an art museum with as strong and coherent a body of work as in Musée d’Orsay, especially as a huge admirer of Impressionism and modern art myself. And to unavoidably compare with the Louvre, the navigation of Musée d’Orsay makes for a far more pleasant and profound experience with what is on display. Of course, the art itself is incomparable, foremost due to the divide in eras. Ultimately, the Musée d’Orsay manifests French art and culture in the modern context at its most disruptive yet persuasive.

The next three reviews:

Sir John Soane's Museum, London

‘R.I.P. Germain: Jesus Died For Us, We Will Die For Dudus!’ exhibition, Institute of Contemporary Arts

Borghese Gallery, Rome

Yaunt - an abbreviation of my Chinese name

Yaunt Gallery - the end goal